Episode 8 begins a block of five short films on city life as it’s experienced outdoors, between buildings. Upcoming episodes focus on walkable and memorable streets, the importance of street trees, street-oriented architecture, and parks, greenways and blueways.

The public realm

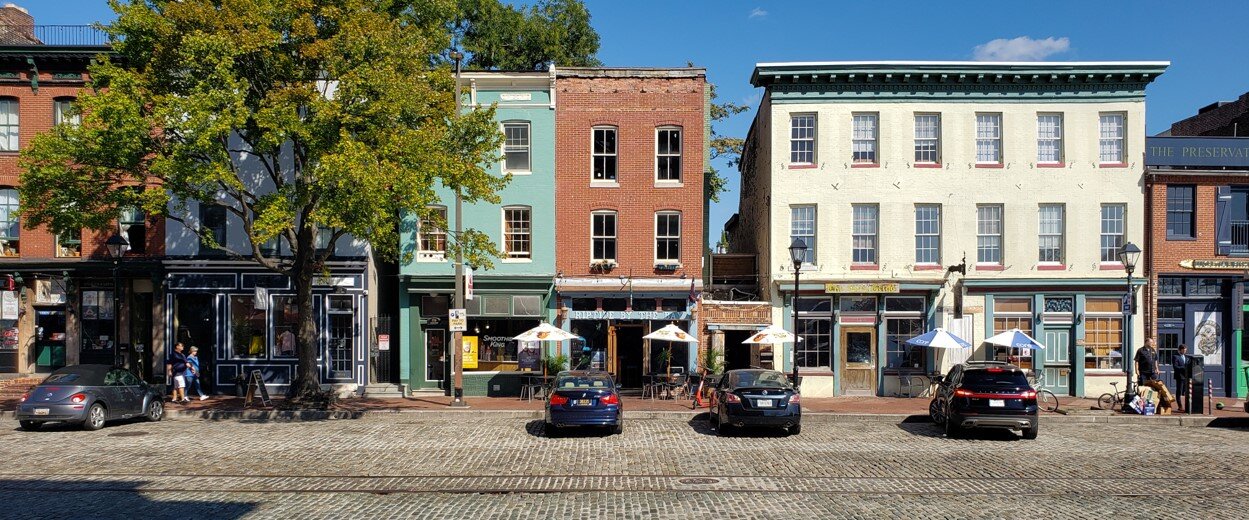

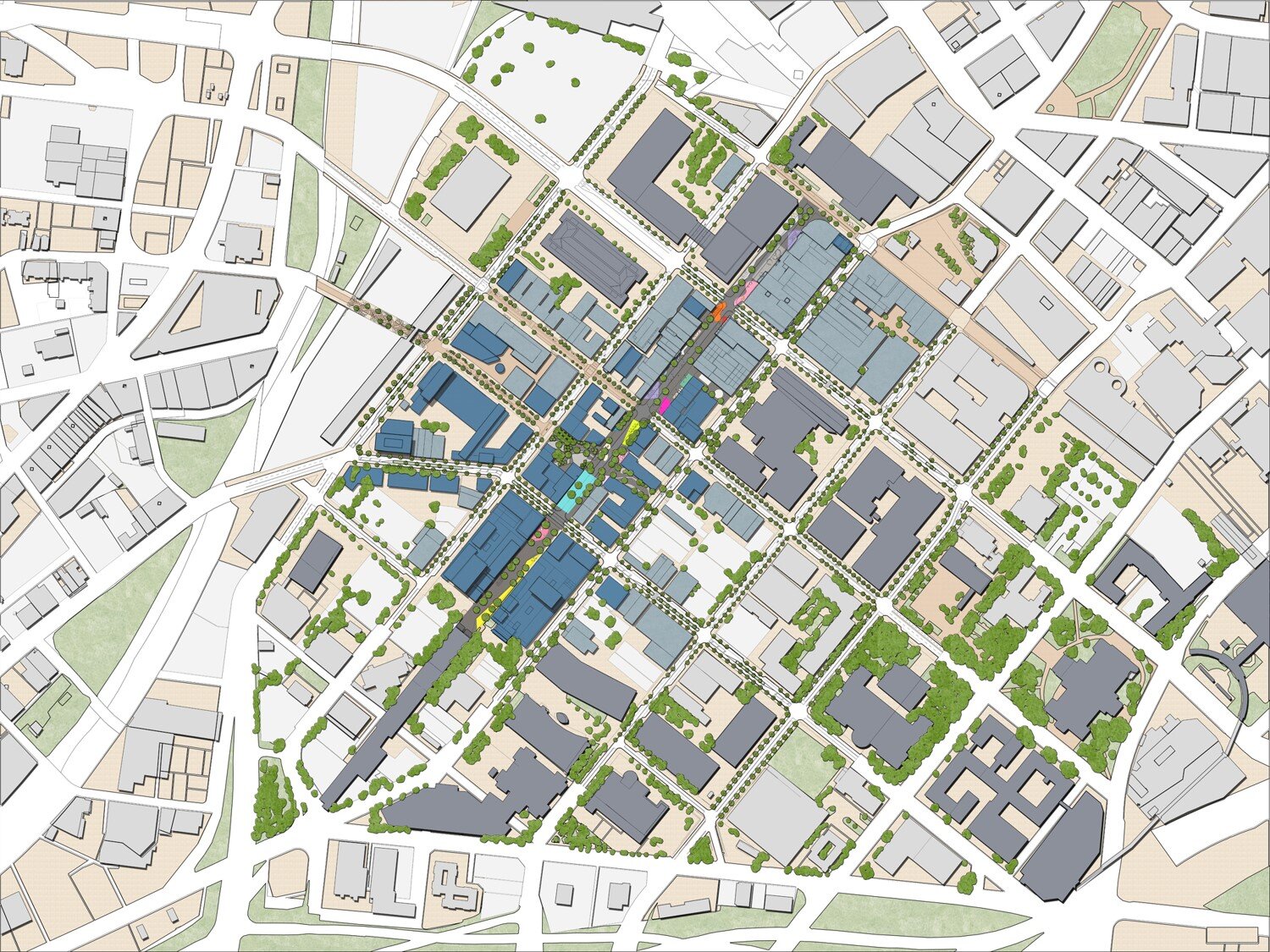

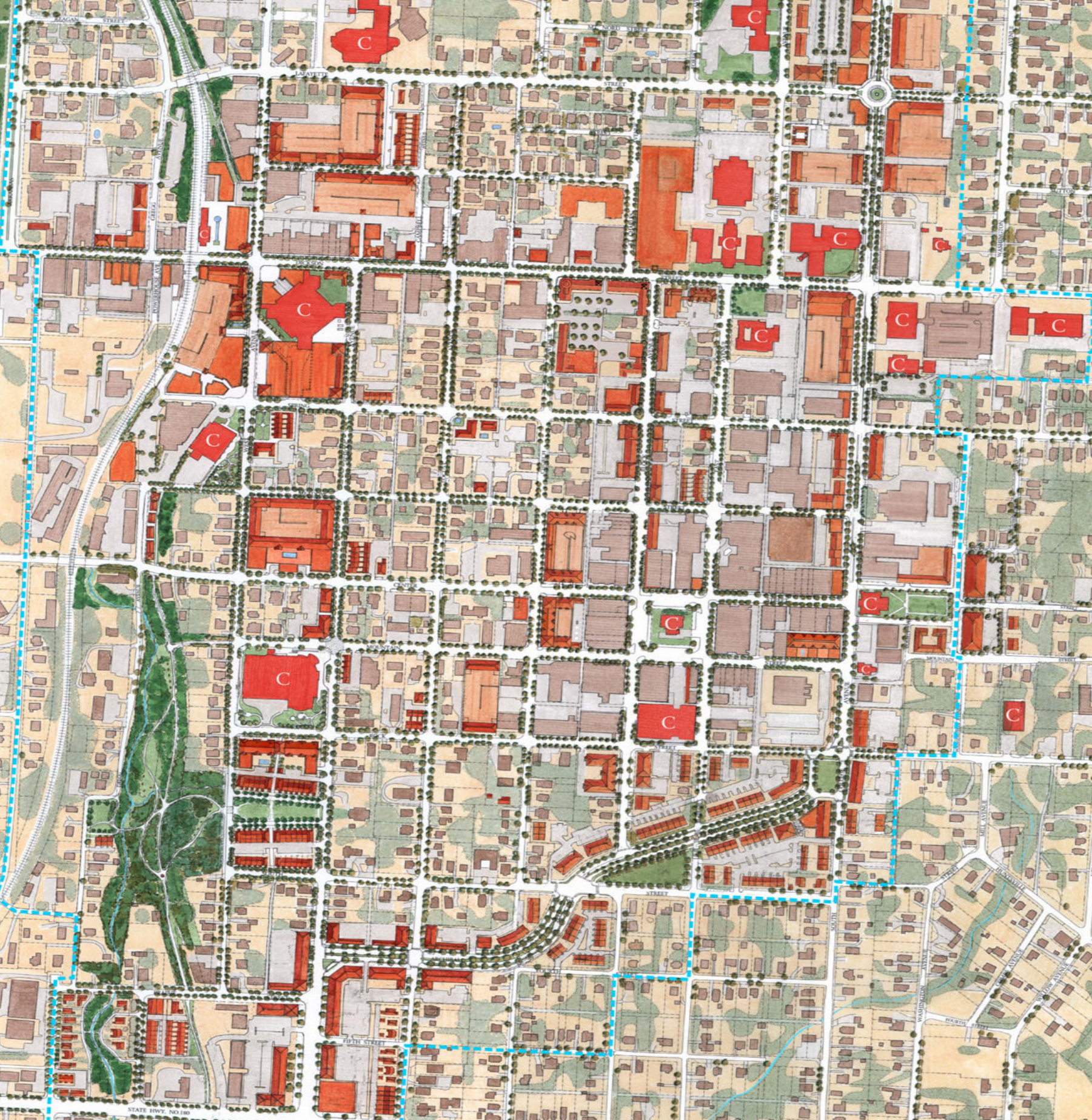

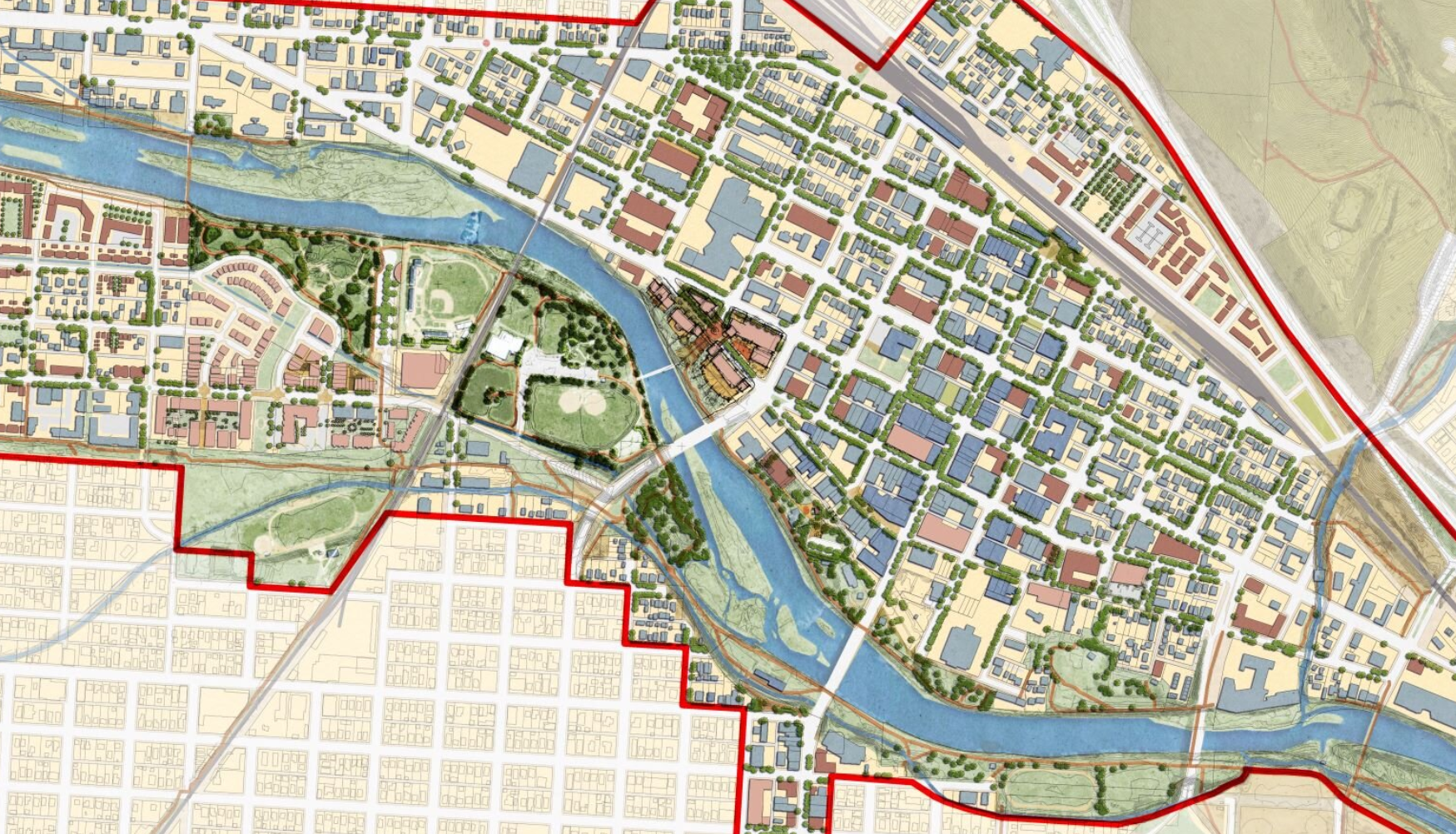

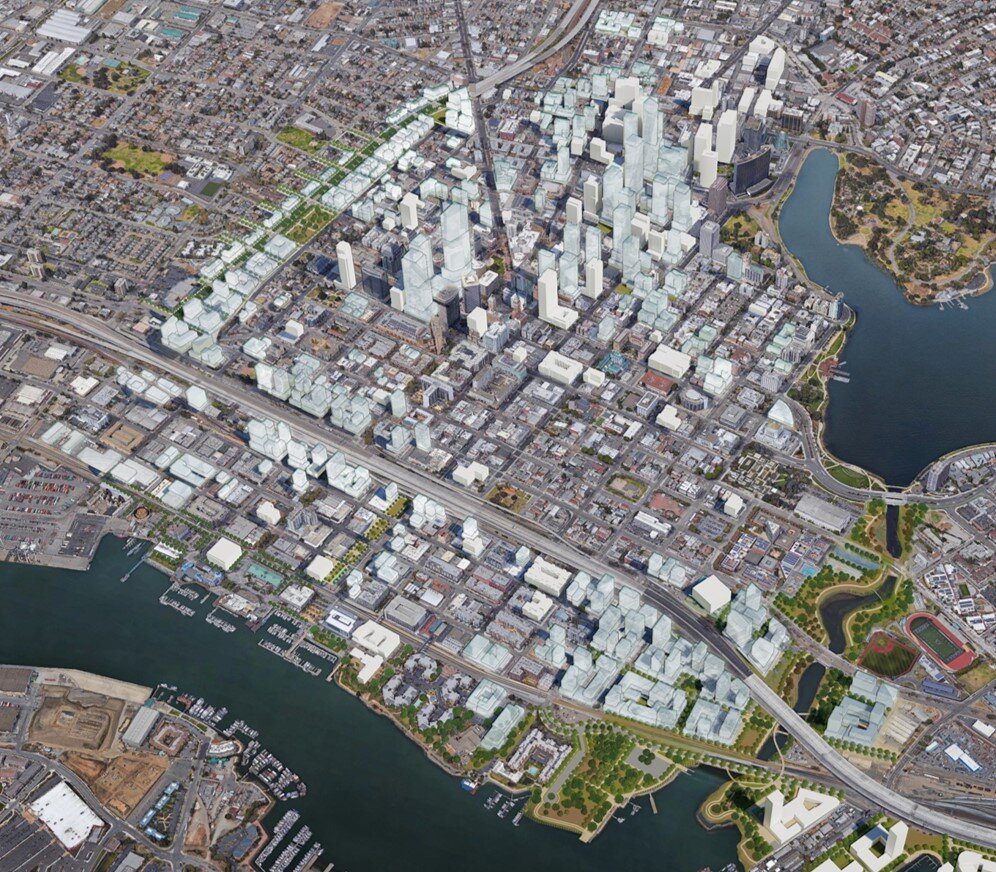

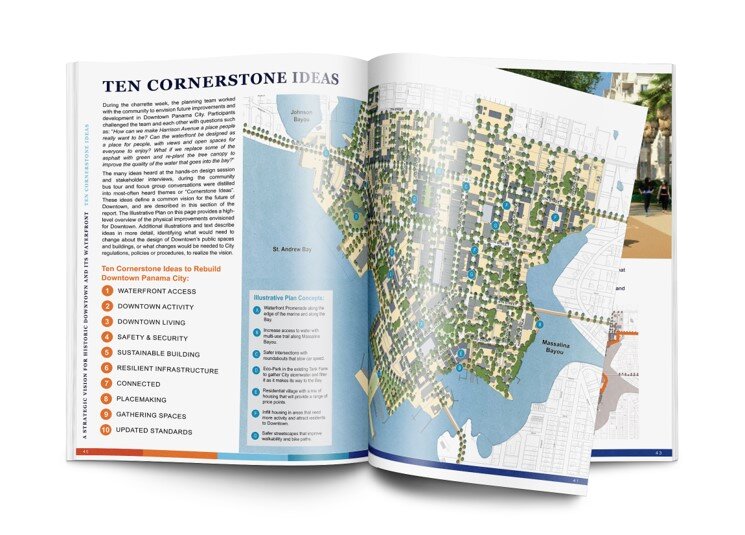

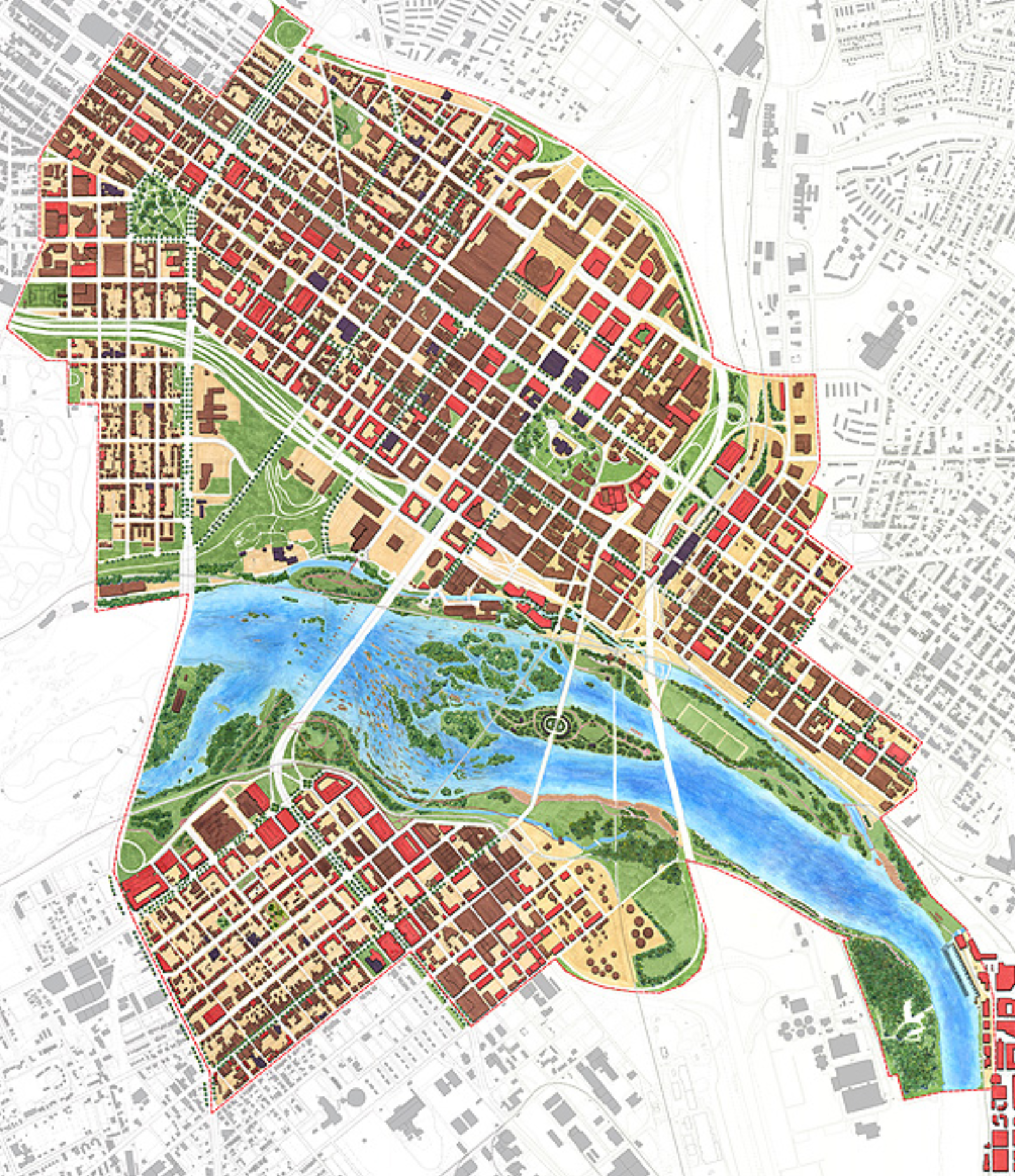

Towns and cities speak to us through their outdoor spaces—the public realm, the world between the buildings. Those public spaces, whether street or parks or squares or plazas, are composed, given their shape and focus, by the design and placement of buildings and the landscape. There’s usually a sense of enclosure and completeness where the public realm is strong. Sometimes the space is narrow, sometimes wide, at times intimate, at times opening up to and contrasting with long vistas.

Street-oriented architecture is a vital ingredient for a positive experience in the public realm.

Your city is a communications device. It’s sending you a message. Is it welcoming people?

Wide or narrow, as you move about the neighborhood day to day, the public realm is where you’re spending your time. And when that public realm is thoughtfully planned and designed, it sends you a message of confidence and comfort and neighborliness. It’s where memories are made, where friends can meet, where ideas are exchanged, where commerce and art and culture and civic life intersect.

Caveat: It could be sending everyone the wrong message.

Warning: Your public realm could be sending all the wrong signals

It’s easy, however, to get it all terribly backwards, and when the public realm is starved for attention and quality, it sends exactly the opposite message: that this is a place where nobody cares, a message of uncertainty. The public realm is where our impressions of the whole city or countryside are formed— for good or ill.

The public realm is just as important in rural places

Experiences

What experience is your neighborhood offering?

The public realm is crucial everywhere, but it’s especially so in cities that need to attract population and investors for revitalization, and in tourist destinations. Give people a good experience, and they’ll return, and help you build a stronger economy, a better tax base, and a creative culture.

If you want people to return, your public realm has to exude confidence. The design is crucial.

The public realm matters, so whether you’re a mayor or a real estate developer or just a taxpayer, it needs your attention. That’s #8 on my list of Town Planning Stuff Everyone Needs to Know. For more information, check out the Dover Kohl YouTube channel. —Victor