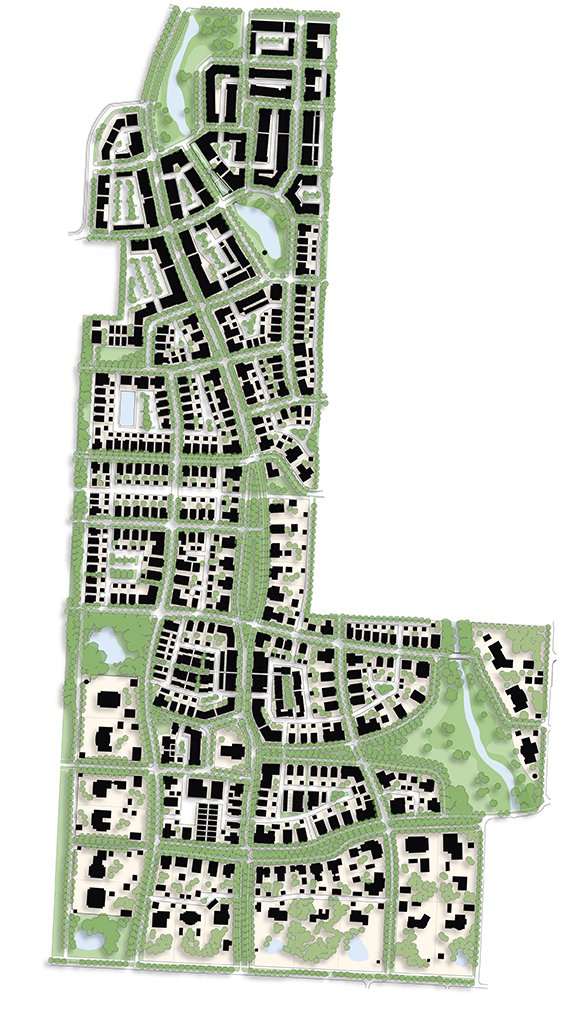

An integrated stormwater canal within the North neighborhood of Warren Park. Dover, Kohl & Partners, 2022

Warren Park Illustrative Plan

A subtle slough wandering through the hay bales, a vast and dancing meadow of wildflowers, and a perfectly pale blue Arkansas midday sky met the Dover, Kohl & Partners team as they first started laying out the future for 197 acres of Northwest Arkansas pastureland. The Warren Family farm’s natural charms and connectivity to Rogers, Bentonville, and the Razorback Greenway together make for fertile grounds in planning the next great NWA community.

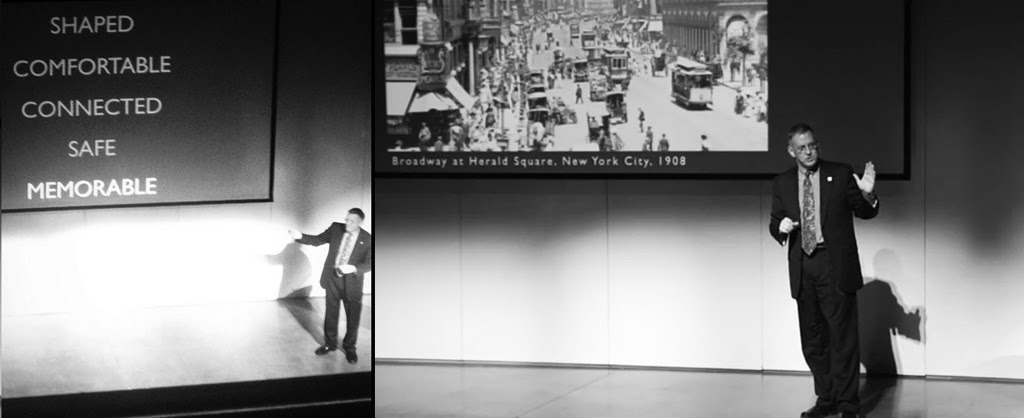

The Dover, Kohl & Partners-led design is essentially two, five-minute neighborhoods large – one North and one South – taking advantage of the existing topography and canopy to create accessible urbanism for a wide variety of households and businesses interlinked through public space. This “Village of Gardens” is inspired by the many great historic American planned neighborhoods of the early 20th Century and their European originations. Places like Mariemont in Ohio and Forest Hills Gardens in New York with their view-framing street deflections and grand public greens or the classic architecture of the Cotswolds and Bath that inspired them in turn. These examples create the foundation for settling a town in the rolling foothills of the Ozarks and are just as relevant to Bentonville as they are Bruges with a strong organization around site context and architectural regionalism.

View from the boutique hotel balcony toward the canal biergarten and event space

Both neighborhoods of Warren Park are centered around public spaces framed with fine-grained building fabric. The northern neighborhood features the more active and commercial areas of the mixed-use program bikeable via the Razorback Greenway and a separated cycletrack. This new Main Street runs a block away and parallel to the existing shallow stream now activated and compressed with canal-front restaurants and boutique hotel rooms while expanded on either end with floodable, passive stormwater parks. The larger of the two stormwater parks lies uphill and when dry serves as a commons for the nearby community center and crescent units on its perimeter.

Grand estate lots are set near the southern neighborhood edges in Warren Park, coupling with long views in public park spaces

Curbside cycletrack along the new mixed use Main Street section of Pinnacle Hills Parkway

The southern neighborhood is centered on a traditional square – complete with a site for a place of worship, grand estate homes, and “missing middle” cottages. The central square and the church project just enough into incoming streets and the network of green spaces to be seen from several blocks away in many different directions. Estate lots on both sides of the neighborhood contain a variety of outbuildings, and on the west side of the neighborhood, face a perimeter trail. Where both the South and the North neighborhood meet, they are joined by West Street, which is designed with a third line of canopy trees shading a multi-user trail; deep front porches will face towards the bikeway.

The Dover, Kohl & Partners team is proud to introduce the plan and some of the inspiration behind it.

Several public spaces will offer unique addresses in the northern neighborhood of Warren Park

A view looking east down West Drive shows its shaded trail, a key connection to the Razorback Greenway